I’ll be honest: when I first read of Robin Williams’ death, it had relatively little effect on me. I try to keep a healthy distance between celebrities and myself, for the sake of my mental well-being. But when I discovered it was a suicide, and then read about the issues he’d been dealing with, I found myself relating to it on multiple personal levels. Struggling with alcoholism, a failed marriage that failed because of decisions you made, depression and anxiety, the facade that gets shown to the rest of the world when you’re crumbling inside – yeah, this was all too familiar.

Required background reading: I wrote about my time in rehab here and my post-suicide stint in a mental health facility here.

One of the reasons I drank as often as I did was the fact that it silenced the multiple voices I had in my head at the same time, and allowed me to focus on one thing for an extended period of time. Without alcohol in me, I found it impossible to concentrate on anything specific for more than a minute or so. In fact, it took about a month and half in rehab before I could summon the ability to do a sudoku puzzle, or read a book. (The good news is that once it comes back, it’s like riding a bike: I was able to read the entire “A Song of Ice and Fire” series during my last two months there.)

(By the way, I know this seems somewhat non-intuitive, since alcohol turns most people into blathering idiots. Just trust me that drugs and alcohol affect addicts differently than non-addicts. Alcohol has the same effect on me that Vyvanse does on my kids for their ADHD: it focuses me, it calms me, and it keeps me awake and aware – despite the fact that it should definitely do the opposite of all of these. There is a reason that “the alcoholic Irish writer” has become such a cliche – I can speak from personal experience that writing is MUCH easier with a couple of shots in me. Most of the articles on this blog (yes, even the ones about recovery) were written when I was in some kind of temporary relapse. Alcohol makes the words flow from the brain and the fingertips in a steady but manageable stream. You would not believe how much I struggled today to even get this started, let alone to finish it while sober.)

For a person that considers themselves intelligent (or talented, or what have you), this is an extremely frustrating situation. I went through it most prominently in my professional career: I design and build web systems. When I got to my worst (2008-2012), I found it nearly impossible to solve even the simplest bug – or rather, to be able to spend the time necessary focusing on one issue long enough to design a solution, write the code, test it properly, and mark it for release. I could get through one of those steps, sometimes – but more often than not, my succint precise design would get lost in the recesses of my mind before I could finish getting the code into the necessary files. Or I’d forget to test vital parts of the program, and I’d introduce new bugs. Or I’d simply lose interest, and spend the day reading political blogs and posting on Facebook instead of actually doing the work I was being paid to complete. Looking at it from the outside, it’s incomprehensible; living inside it was chaotic and frustrating and horribly, horribly discouraging. It should come as no surprise that I went through six jobs in 3 1/2 years, and left none of them on good terms or with a single professional reference.

Now, considering the number of external voices Robin Williams had, I can’t even imagine what his internal monologue was like. I’ve read multiple accounts of how “exhausting” it was simply to be around Williams when he was performing – here and here for examples). So, if was that tiring just for people in his vicinity, just try and wrap your head around what it was like to actually be him 24/7. Does it really come as a surprise that he kept falling back into something he knew was a monstrous mistake, but which was (possibly) the only way he could find a few hours of relative peace?

Is it really a surprise that he eventually decided to take a route that silenced all of the voices, permanently?

I don’t know if my depression was the launching point for my alcoholism, or if my alcoholism turned my mild depression into major (and I’m certainly not qualified to draw conclusions about Robin Williams’ situation either). At this point, it doesn’t matter – they’re completely symbiotic now. In a weird way, I’m “lucky” – I have definitive proof that 1) I can’t just drink socially and not fall off the wagon eventually; 2) a relapse could very easily turn into a suicide attempt; and 3) I have the ability to get and stay sober, and that my life can improve if I do so. I’m also surrounded by friends and family and loved ones who are more than happy to offer support and encouragement, for which I am eternally grateful.

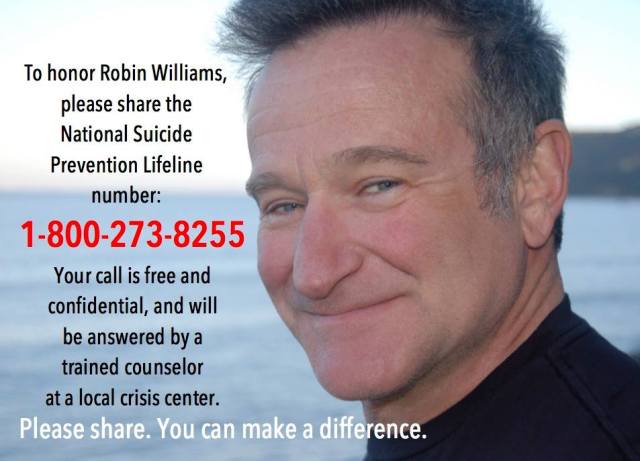

But not every addict does. And not every addict is nearly aware of his/her own issues as I am. So, as a final effort: